Publications & Resources

Here you will find a variety of articles, studies, and publications on AfCFTA that have been published as part of the project or by our partners.

2024

Trade-Unions-in-AfCFTA 2021 A Guide to the AfCFTA

The African Regional Organisation of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUCAfrica), in collaboration with the Labour Research Service (LRS), supported by the Trade Union Solidarity Centre of Finland (SASK), is working to strengthen the capacity of the trade union movement in Africa to engage on matters relating to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). The AfCFTA came into effect on 1 January 2021 and from a population perspective represents the largest free trade area in the world. It has been signed by 54 of the 55 African Union members. There is a multitude of positive projections and ambitions

made with regards to the AfCFTA. It is, among others, expected to lead to the creation of a single African market for goods and services, facilitate the long-awaited free movement of people, mobilize regional investments and be the necessary building impetus towards the establishment of a Continental Customs Union. In the same breath, history and trade unions’

own experiences have taught us that trade liberalization can have detrimental consequences on jobs and a country’s ability to meet the Decent Work Agenda.

2024

The African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement aims to create a single

market for goods and services, increase intra-Africa trade and promote sustainable

socioeconomic development in Africa. African countries need to balance efforts to address

these goals with the urgency of climate change. As of the 27th session of the Conference

of Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2022, most

African countries had submitted their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to

mitigate the impact of climate change. Establishing a carbon market is now on the policy

agenda. This paper uses a dynamic general equilibrium model with different sources of

energy (including renewable energy) and an in-depth presentation of greenhouse gas

emissions to assess the economic and environmental impacts of implementing the

AfCFTA Agreement and adopting various climate policies in Africa, including those NDCs

and the International Monetary Fund’s proposal of carbon price floors. It shows that

implementing the agreement and achieving Africa’s climate objectives are compatible.

Continental coordination of emissions reduction among African countries proves most

efficient for climate action.

2024

UNECA 2024 AfCFTA Implementation Strategies synthesis report

This Synthesis Report on AfCFTA implementation strategies forms part of the background documentation for the Peer Learning Conference on AfCFTA implementation strategies, held on 15 to 17 January 2024 in Nairobi, Kenya. The report is intended to provide a snapshot of AfCFTA implementation strategies in the continent and serve as a background document to inform discussions among the participants. To this end, the report provides highlights of adopted strategies focusing on their core elements, the process by which they were developed and adopted, and national experiences to date in the implementation of these strategies.

2024

African Continental Free Trade Area

Africa is in the spotlight. The establishment of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) promises to turn Africa into a modern, industrialized, cohesive, and influential player on the global stage. A modern Africa—one that is no longer depleting her mineral wealth to export to foreign markets, but instead industrializing her economies, incubating the entrepreneurial zeal of her burgeoning youth population, and giving her people a chance to live a better life—is a dream whose time has come. The AfCFTA aims to utilize trade as an engine of growth and sustainable development by boosting intra-Africa trade. The AfCFTA is more than a pledge to eliminate tariffs, cut red tape, or simplify customs checks. It is a unique opportunity to create an integrated, continentwide market and a vital step toward building.

2024

Production Transformation Policy Review of Egypt

The current global economic and political setting is turbulent, complex and fast-changing. Governments, businesses and societies are engaged in better understanding the ongoing technological, digital and industrial reorganisation processes and their profound potential impacts on the economy and the society. At a time in which it is clear that growth is a necessary, but not exclusive, condition for development and that incentives are needed to guarantee that growth is inclusive and sustainable, planning and implementing strategies for economic transformation become paramount. This is even truer in the middle of the global COVID-19 pandemic that has exposed the vulnerabilities of the global economic system.

2024

African (De)Industrialisation and the AfCFTA

Industrialisation has long been on the policy agenda in Africa, although success has mostly failed to materialise. Studies find a historical tendency towards deindustrialisation in Sub-Saharan Africa (Jalilian & Weiss, 2000) and a constantly declining share of manufacturing and industry value added, a trend that has continued in recent years (Aryeetey & Moyo, 2011).

This is all the more worrying, given that structural change (defined as shifting labour and capital from low productivity to high productivity sectors of the economy (Tregenna, 2015)) has been shown to be the key driver of economic development.

2024

Labour Market Effects of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA)

The African Continental Free Trade Area marks a historic decision on the road to regional economic integration on the continent. If implemented, the agreement has the potential to make a significant impact on improving the livelihoods of the African people, by increasing intra-African trade and generating new employment opportunities on an integrated African labour market.

2024

AfCFTA – African trade pact launched

Launch of the AfCFTA The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has entered into force. The world´s largest free trade area in terms of participating members was officially launched on 7 July 2019, during the African Union (AU) Extraordinary Summit in Niamey, Niger. It had come into force on 30 May 2019, after 22 countries had deposited their ratifications with the AU Commission and the minimum threshold had been reached.

2024

THE GUIDED TRADE INITIATIVE: DOCUMENTING AND ASSESSING THE EARLY EXPERIENCES OF TRADING UNDER THE AFCFTA

The primary purpose of this research is to provide practical

information on the Guided Trade Initiative (GTI) based

on empirical data gathered from the experiences of

participating State Parties and companies. The findings will

serve as a springboard for further research and contribute

to strengthening the implementation arrangements of the

AfCFTA, ultimately increasing African trade.

2024

Gender and Value Chain-Driven Industrialisation Under the AfCFTA

This report draws together themes that have been covered in prior tralac research within the gendered value chains project and attempts to create an overall synthesis of the various data-driven themes of this research.

2024

Empowering Women through AfCFTA

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) represents a significant stride toward economic integration across Africa. Since trading commenced under the AfCFTA framework in January 2021, the initiative has been geared towards establishing a unified market for goods and services, enabling the free movement of businesspersons, and facilitating investments throughout the continent. By lowering trade barriers, AfCFTA aims to bolster economic growth, expand employment opportunities, and enhance Africa’s competitive stance on the global stage

2024

Africas Development Dynamic

The annual flagship report Africa’s Development Dynamics provides the latest information on economic policies on the African continent and in its five regions. It proposes a new narrative assessing Africa’s economic, social and institutional performance in light of the targets set by the African Union’s Agenda 2063. This 2023 edition explores how Africa can attract investments that offer the best balance between economic, social and

environmental objectives.

2024

AFCFTA-Creating One African Market

Following the adoption of the Agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) in March 2018, the Agreement legally entered into force in May 2019. This wassubsequently followed by the launch of trade on 1 st January 2021. Commercially meaningful trade, thereafter, commenced in October 2022 using AfCFTA preferential tariff regime and trading documents.

2024

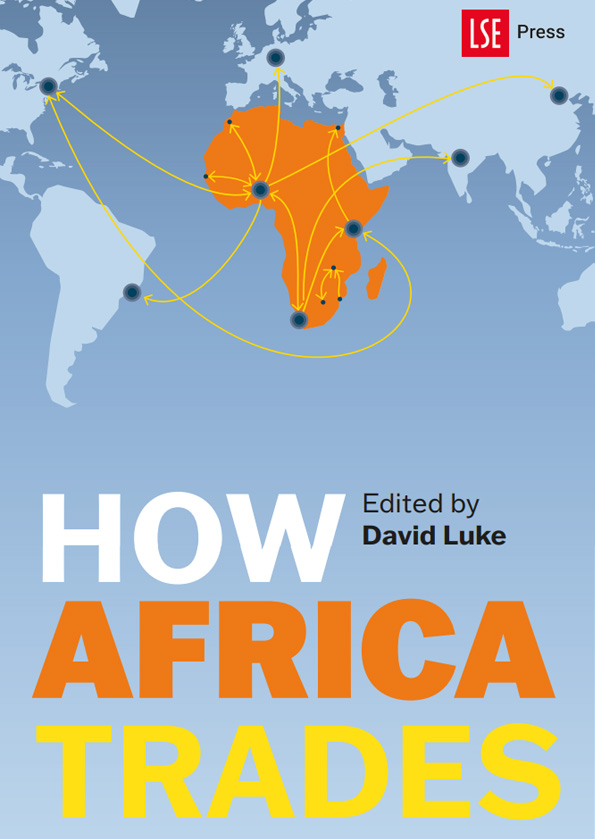

How Africa Trades

Welcome to How Africa Trades, which seeks to enhance understanding of the

role of trade in Africa’s development. It is our expectation that the book will

contribute to an extension of the current knowledge base on African trade

policy for more informed deliberations on trade as a driver of growth and

economic transformation at various levels of policymaking, advocacy,

and scholarly and pedagogical pursuits.

2023

Tunisia: macroeconomic and trade profile

More than decade after the 2011 Tunisian revolution, the country continues to be challenged by a fragile political environment, and it is yet to reap the economic benefits of efforts towards democratic transition. The Tunisian economy grew by 2% on average per year from 2012 to 2019, lower than the 4% average annual growth in the decade before the 2011 revolution1 (IMF, 2021b). The Tunisian economy has been dominated by the services sector, which represented about 63% of gross domestic

product (GDP) on average from 2011 to 2019, followed by manufacturing (16.3%), agriculture (10.2%), mining and utilities (5.9%) and construction (4.6%). 2 After the revolution, the share of the mining and utilities sector in GDP declined to 5.7% (average 2012–2019) from 9.6% in the previous decade (average 2001–2010). 3 While the share of population living in extreme poverty at less than $2.15 (2017 purchasing power parity, PPP) a day has remained below 1% (Table 1), the share of the ‘vulnerable’ population living below $5.50 a day increased from 16.7% to 20.1%, or about 2.4 million people, in 2020 (World Bank, 2021). Unemployment has been persistently high in the past decade (2010–2021), at 15.8%, with disproportionate impact on women (23%) and youth (37%) (ILO, 2021), contributing to continued social

tensions.

2023

Democratic Republic of Congo: macroeconomic and trade profile

DRC is the largest country by land area in sub-Saharan Africa and has a strategic

location sharing a common border with nine countries.

1 The country is endowed with

natural resources including minerals such as cobalt, copper, tin and tungsten;

hydropower potential; arable land; a large young population; and immense

biodiversity (World Bank, 2022a).

2023

Ghana: macroeconomic and trade profile

The Ghanaian economy grew at 6.6% per year on average from 2011 to 2019,

above the average growth rate in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) (5%) and

sub-Saharan African countries (3.5%) during the same period.

1 Growth has been

traditionally anchored by the agricultural as well as the mining and utilities sectors,

contributing to 37% of total value added on average from 2016 to 2020 (UNDESA,

2022). Notably, the share of the mining sector in Ghana’s total value added

increased from 3% in 2010 to 14% in 2019, while the level of the sector’s

employment fell, highlighting the challenge involved in having a sizable portion of

growth that has not generated many jobs (World Bank, 2021)

2023

Rwanda: macroeconomic and trade profile

Rwanda has achieved significant economic and social development gains since the 1994 genocide and civil war (Table 1). The Covid-19 pandemic, however, gravely affected the country’s tourism, services and industrial activities, inducing a decline in gross domestic product (GDP) by 3.4% in 2020 (IMF, 2021a). In 2021, GDP rebounded strongly, with 10.9% growth (at par with pre-pandemic 9.5% growth in 2019), supported by accelerated vaccination, the lifting of restrictions, recovery of external demand for Rwandan exports and accommodative policies (IMF, 2022a).

Rwanda’s announced Covid-related spending reached $1 billion (10.1% of GDP), higher than the packages of low-income countries (4% of GDP) and close to those in emerging markets (9.9% of GDP). 1 In August 2021, Rwanda raised $620 million from 10-year Eurobond issuance to finance the country’s Covid-19 recovery, refinance debt maturing in 2023 and fund strategic investments (MINECOFIN, 2021). Rwanda’s Covid-19 fiscal package was assessed to have limited the impact of the crisis (IMF, 2021b) but may have contributed to a significant rise in public debt and inflation, which remained elevated in 2021

2023

Ethiopia: macroeconomic and trade profile

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, with a population of 118

million,

1 and is a development success on several measures (Table 1). Prior to the

Covid-19 pandemic, Ethiopia was one of the fastest-growing economies in the world,

and the fastest-growing in Africa, with an annual growth rate of 9.1% over the decade

to FY 2019/20.

2 This economic growth was influenced by a shift in government

strategy in 2010 from agriculture-led to manufacturing-led growth, supported by

significant public infrastructure investment (see MoF,3 2010; Haile, 2018; World Bank,

2022a). The growth was accompanied by longer years of life expectancy, gradual

poverty reduction, a reduction in gender inequality and an overall improvement on the

Human Development Index.

2023

Niger: macroeconomic and trade profile

Niger is a least developed, landlocked country in West Africa. It is also one of the

poorest nations in the world, and has among the lowest levels of human

development (Table 1).1

It is estimated that half of its 25 million population was

living in poverty (under $2.15 a day) as of 2021 (World Bank, 2022a). With a great

part of its territory covered by the Sahara Desert, Niger is extremely susceptible to

locust invasions, recurring drought and gradual desertification (Pinto Moreira and

Bayraktar, 2005). More than 75% of the workforce are in subsistence agriculture,

exposed to the adverse effects of climate change (World Bank, 2022a; 2022b).

Since Niger’s output is driven largely by agriculture and mining activities, economic

growth is vulnerable to climate and external demand shocks. In this context, gross

domestic product (GDP) growth has been volatile, ranging from 2.4% to 10.5%

between 2011 and 2020.

2023

Malawi: macroeconomic and trade profile

Malawi is a landlocked, least developed country in south-eastern Africa, bordered

by Mozambique, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zambia. The country has one

of the highest poverty rates worldwide, with more than 70% of the population living

on less than $2.15 purchasing power parity (PPP) a day as of 2019 (Table 1), and

low levels of human development (ranking 169th of 190 countries on the Human

Development Index) as of 2021 (UNDP, 2022). The country had relatively higher

shares of gross domestic product (GDP) from services (52.4%) and industry

(18.4%) as of 2021 (World Bank, 2022c). However, 76% of total employment

remained concentrated in the agriculture sector as of 2019, potentially driven by the

82% of the population living in rural areas as of 2021 (ibid.). Heavily dependent on

rain-fed agriculture to maintain food security (WTO, 2016), Malawi has

2023

Côte d’Ivoire: macroeconomic and trade profile

Since the end of the political crisis in 2011, Côte d’Ivoire has been one of the fastestgrowing countries worldwide, with annual growth of 8.2% of gross domestic product

(GDP) between 2012 and 2019.

1 The International Finance Corporation (IFC) has

highlighted five key elements that contributed to this sustained growth: acceleration of

public investment; strong agricultural production and diversification of agricultural

exports; increased foreign direct investment (FDI); improved access to digital

services; and improved access to electricity at low prices (albeit with disruptions in

late 2020 to August 2021) (IFC, 2020).

2 Poverty, employment and income per capita,

which deteriorated at the peak of the political crisis in late 2010, have improved

substantially in the post-conflict period

![[Executive Summary] Effects of the AfCFTA for German and European Companies](https://oneafricanmarket.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Effects-of-the-AfCFTA-for-German-and-European-Companies.jpg)

2022

[Executive Summary] Effects of the AfCFTA for German and European Companies

In May 2019, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement entered

into force. In numerous respects, the AfCFTA can be considered a historic milestone towards trade liberalization on the African continent. Following ten rounds

of official negotiations beginning in June 2015, the agreement now spans 55 African

Union Member States of which 43 have already deposited their instruments of

ratification.1

By connecting these economies, AfCFTA has become the largest trading bloc in the world in terms of market size, covering more than 1.3 billion consumers with combined GDP of USD 2.5 trillion. The AfCFTA’s core objective is to

deepen the economic integration of the African continent by creating a single market for the movement of goods, services, capital and natural persons. In the study

“Effects of the AfCFTA for German and European companies”, we assess the status

quo of trade within AfCFTA economies and between AfCFTA and EU

economies, and outline three hypothetical future outcomes of AfCFTA for different

levels of trade liberalization

![[Study] Effects of the AfCFTA for German and European Companies](https://oneafricanmarket.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Effects-of-the-AfCFTA-for-German-and-European-Companies-Study.jpg)

2022

[Study] Effects of the AfCFTA for German and European Companies

In May 2019, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement entered into force. In

numerous respects, this agreement can be considered a historic milestone towards trade liberalization

on the African continent. Following ten rounds of official negotiations beginning in June 2015, the

agreement now spans 55 African Union Member States of which 43 have already deposited their

instruments of ratification.1 By connecting these economies, AfCFTA has become the largest trading

bloc in the world in terms of market size, covering more than 1.3 billion consumers with combined GDP

of USD 2.5 trillion. It is expected to support African economies achieve rapid industrial development,

diversify their export baskets and make progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs). These ambitions are reflected in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 as well as recent statements

from the Secretary-General of the AfCFTA Secretariat.2